Are PRISon Libraries Motivators of Prosocial Behavior and Successful Re-entry?

A Collaboration Between Library Research Service (Colorado State Library – Colorado Department of Education), Institutional Library Development (Colorado State Library – Colorado Department of Education), Colorado Department of Corrections, Remerg, and Renewed Libraries

Authors:

Charissa Brammer, Amy Bahlenhorst, Sara Wicen, Chelsea Jordan-Makely

Introduction

Do prison libraries help people? If so, then how? A team of researchers from the Colorado State Library’s Library Research Service (LRS), Colorado Department of Corrections, Remerg, a Denver-area re-entry nonprofit and an independent library consultant, Renewed Libraries, led the PRISM Project which aimed to discover, “Are PRISon Libraries Motivators of Prosocial Behavior and Successful Re-entry?” The PRISM Project used mixed methods–focus groups inside prisons in Colorado, as well as with previously incarcerated people, and surveys, also with both populations. The study focused on the outcomes of prison library services, centering the experiences of people who have been or are currently incarcerated to determine the significance of the prison library to them, both inside and outside of prison. This research will help move the discussion of prison library impacts from anecdote to data and fill a gap in research on the subject.

This project was funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) and spanned the years 2022-2025. This dataset helps to build a long-overlooked outcomes-based understanding of prison libraries in the same vein as impact studies that are increasingly common in academic, public, and school libraries to show how libraries help or change people or communities. We hope that this research will help to build a foundation for outcomes-based research in prison libraries that will help prison library staff, departments of corrections, and librarians to better understand prison libraries, patron needs, and how to improve services.

This study focuses on prosocial behaviors, defined by CDOC as “positive social interaction with employees and contract workers, family members, and other offenders that respects the rights and boundaries of other individuals” (2025, AR 0650-04), and how those behaviors might impact the lives of people in prison and their ability to successfully re-enter society. Research shows that the vast majority of people who are incarcerated will be released from prison (Ositelu, 2025, p. 1), thus understanding how the library might help them prepare to successfully return to their families and communities is crucial to the work of prison libraries.

Focus groups took place in 2023, as facilities were beginning to reopen and library services were resuming after being on lockdown for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic. Surveys were subsequently administered from 2023-2025. Surveys are still being analyzed and will not be covered in this paper. The focus groups with people who are currently incarcerated were led by researchers from the Library Research Service (LRS, an office of CSL), while Remerg facilitated groups with those who were recently incarcerated.

A team of LRS staff and an outside library consultant from Renewed Libraries analyzed data from focus groups and surveys as these data became available. This grounded-theory approach enabled the team to adjust the survey instruments and to develop a codebook grounded in the empirical insights gained over a three-year period. The codebook was initially established using the guiding research questions from the IMLS proposal:

- What are the outcomes of prison library use, and in particular, those related to prosocial behaviors, information literacy and learning skills, and preparing for successful re-entry to the community?

- What types of collections, programs, and services are associated with positive outcomes of prison library use in the view of the service users?

- In what ways can prison libraries be improved, either by increasing the variety of positive outcomes to which they contribute or by improving their effectiveness in contributing to current, known outcomes?

This research is designed to be replicable in different prison contexts in the United States, which vary widely from state to state and system to system. To facilitate this, the research team created a toolkit that includes the survey instruments, a sample codebook, and tips to help other researchers succeed in replicating the PRISM Project in other settings. As stated, this project was highly collaborative and demonstrates that librarian-researchers can enter different prisons to conduct focus groups, provide access to online and paper surveys in the appropriate language to people who are currently incarcerated, conduct focus groups, and deliver surveys to people who were formerly incarcerated by leveraging the connections and knowledge of people currently working in the re-entry services community. This can all take place without creating security issues or unreasonable disruptions to library services , and it can yield results that build understanding of how libraries in prisons work, how they can be improved, and what they mean to people who are living in prisons and those who have returned to society.

Once all data collection was complete, the PRISM study included 62 focus groups — 54 from inside Colorado facilities and eight conducted with people who were previously incarcerated. We also received 271 surveys from formerly incarcerated people, plus 456 from currently incarcerated individuals. This report focuses on the data gained from the focus group interviews, with the analysis of the surveys to be concluded in 2025.

Executive Summary

The PRISM study succeeded in identifying outcomes of prison library use, the services that led to those outcomes, and ways for prison libraries to improve. Above all, the sentiments regarding prison libraries from both currently and formerly incarcerated people were overwhelmingly positive. Even while identifying barriers to use and thoughts for improvement, focus group participants were resoundingly thankful and positive when describing their experiences.

This project also aimed to identify prosocial behaviors associated with prison library use. Thirteen prosocial behaviors were identified in focus group transcripts in total. This analysis focuses on four of these:

- Connection with others

- Respect for others/property

- Expressing appreciation

- Helping others

Instances of connecting with others were frequently identified in 85% of transcripts and were a direct result of time spent in the library with other residents, staff, and loved ones outside of prison, or engaging with materials checked out from the library. Many participants expressed appreciation and gratitude for their experiences with the library, and for their interactions with library staff. Respect for others/property was shown in regards to the library space, materials and people inside the library. Participants described behaving differently in the library because they respected the library space and staff.

Self-regulation was a prosocial behavior that occurred when people opted to remove themselves from negative situations and instead engaged with the library or library materials. Self-regulation was used as a coping mechanism and was therefore closely related to the code “mental health.” Statements coded with “mental health” included instances of people using the library to stay sane, sharp, and optimistic. “Behavior modification” was often coded alongside “mental health.”

Behavior modification due to opportunities to visit the library was identified in roughly 75% of transcripts. Some people modified their behavior in order to stay out of trouble and maintain library privileges, whereas others found that library use changed their perspectives, moods or thoughts, which in turn influenced their behaviors, too. Behavior modification was regularly identified alongside the code “library as a place of peace.” This was often in cases where people had changed their behaviors inside the library in order to maintain an environment of peacefulness, which was unlike the rest of prison. This escape from the normal, loud prison environment was an extremely common theme throughout the research. “Escapism” was the second most common reason that people inside used their prison library and allowed people to dissociate from their current situation. “Passing time” was another common reason for library use, but the most common reason was for information access. “Information access” was the most frequently applied code in all of the transcripts.

Closely related to information access were the codes “self-led learning” and “literacy.” People engaged in self-led learning in order to broaden their horizons, find self-help, and build skills for use in prison and upon re-entry into society outside of prison. Improving literacy was another type of self-led learning and outcome of prison library use.

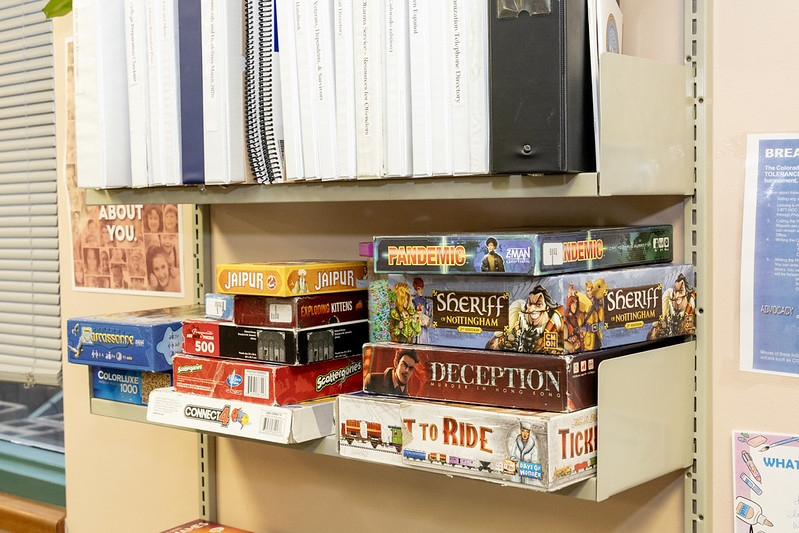

The above outcomes were made possible thanks to a variety of collections, services, and programs. Focus group participants mentioned a wide variety of these, but a few stood out among the rest. “Collection” was the second most frequently coded library service and referred to any cohesive group of materials within the library. The library collection helped people learn as well as access information. As mentioned above, “information access” was very prevalent in discussions of reasons for prison library use. A subset of this, “re-entry information,” was far less prevalent, but still extremely important when available.

“Music” (a type of collection) was an unexpectedly common code. Listening to music in the library gave people a rare sense of autonomy and was commonly coded alongside “mental health” suggesting a relationship between the two concepts. Reading materials were a more obvious collection mentioned by participants and a wide variety of titles and topics were shared. These materials accessed in the library helped people develop empathy, which was one of the prosocial behaviors identified.

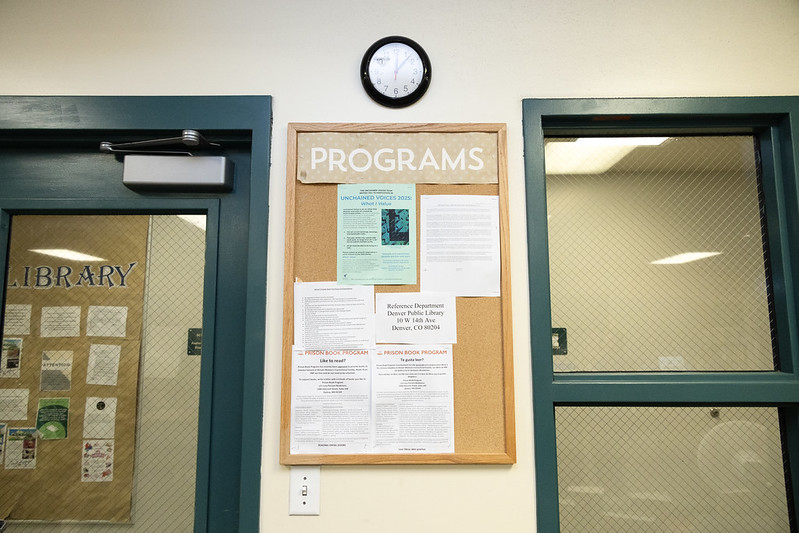

Library programs were undergoing a shift during the focus groups; the loosening of restrictions in a post-COVID world had just recently allowed for the return of some prison library programming which had been sorely missed. Read to the Children stood out as a highly valued program that allowed people to engage in many prosocial behaviors including connecting with others, role modeling, expressing appreciation, social norms/normalization, and agreement. The importance of this program in peoples’ lives really cannot be understated.

Though many library services were identified, three were most closely related to the outcomes of library use outlined above. Staff were of utmost importance to focus group participants. The way that library staff treated patrons was often identified as uniquely positive compared to other staff and resident interactions that emphasize the power dynamics within the prison atmosphere. Library staff were regularly found to be helpful, kind, and vital to the overall success of a prison library.

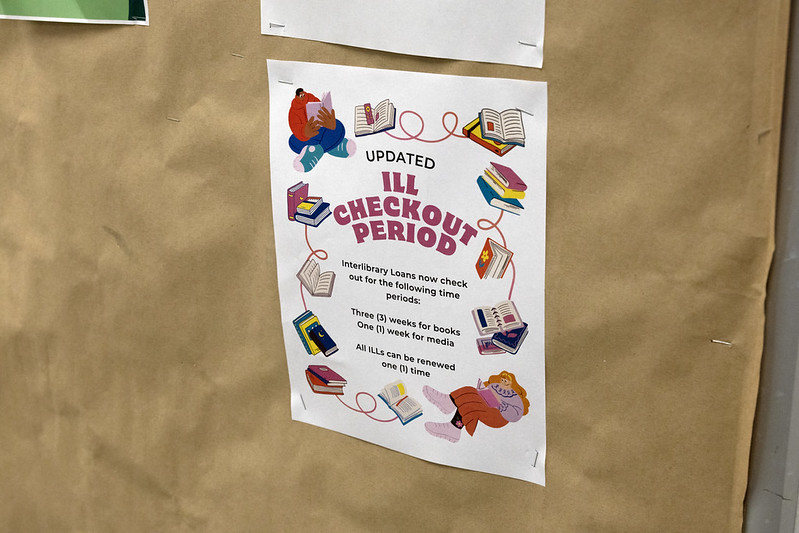

A surprising finding in the research was the importance of “soft seats” as a library service. Soft seats were often mentioned when describing the “library as a place of peace” and were found to provoke positive mental shifts for people. Interlibrary loan as a library service also cannot go without mentioning. In libraries with limited collections, access to this service was vital in order to fulfill patron’s information and recreation needs.

Despite the many positive experiences with prison libraries, there remain many barriers to use and avenues for continued improvement. “Barriers to use” was the third-most common code used for the inside focus group transcripts, and the second for outside transcripts. Barriers included policies, security restrictions, poor collections, lack of information about the library, staffing shortages, and discouragement from staff. With these barriers come ideas for improvement.

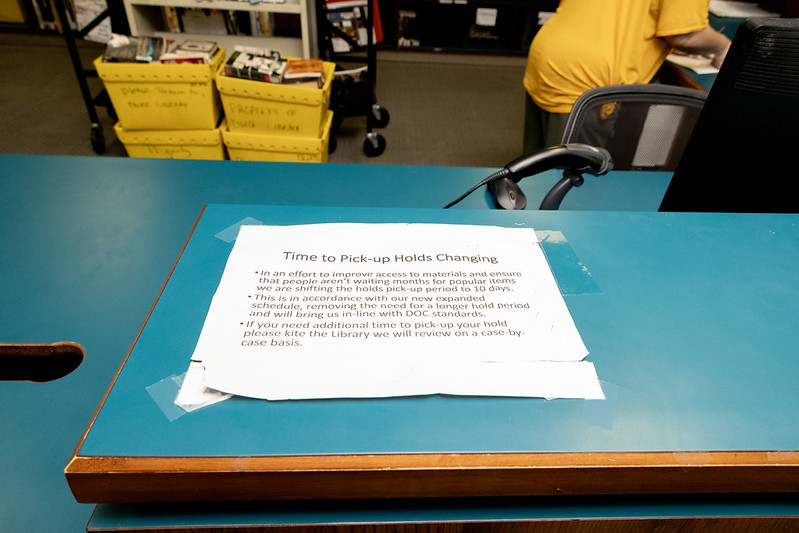

Collection quality and quantity were two areas identified for improvement. The importance of a high quality collection is underscored by the ties between collection and social connection, as shown by the outcomes of prison library use. Related to this, censorship was mentioned as a policy that created a barrier. The lack of access to newspapers and periodicals created an information gap and widened the divide of connecting with others on the outside. Similarly, the lack of re-entry information from the library was regularly mentioned, as was access to modern information in general. The library catalog was identified as a barrier because it was cumbersome to use, and unhelpful for discovering new resources. Some prison libraries do not have any catalog access at all, or people are unaware that it exists. Requests had to be passed through library staff.

Library staff are immensely important to the success of a prison library, and the irregularity and inability to meet staffing standards was identified as a barrier. Library staff both literally and metaphorically hold the key to the library, and therefore the information and enjoyment within. Beyond this, additional training for current staff could also help improve customer service, reach more people and increase the library’s potential reach. Though not frequent, a few people did mention instances of negative interactions or relationships with library staff as well as experiences of discomfort or violence between patrons that prevented them from using the library. Unmet staffing needs as well as policy restrictions due to COVID and other factors also meant that library programs were insufficient in the eyes of many. The power of library programs to foster prosocial behaviors is important, and more programming was requested regularly.

Though this study cannot draw causational conclusions, our findings indicate that prison libraries are in fact motivators of prosocial behavior and in turn, assist people in successful re-entry. The collections, services, and programs that the library provides are invaluable to their patrons, and the effects of these are felt long after re-entry. As with any library, there remains gaps in service, and many opportunities for improvement. The information learned, connections built, and positive mental and behavioral health changes made thanks to prison libraries all contribute to the development of a wide variety of prosocial behaviors and without a doubt assist people in re-entry.

Literature Review

The history of library services for incarcerated people in the United States dates back at least as far as 1870, with shifting aims, ebbs, and flows since that time (Austin, 2022). The first nationwide standards for library services for incarcerated people were established by the American Library Association (ALA) in 1944, and have been periodically revised and updated since, most recently in 2024. Further to these Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained, the ALA’s Prisoner’s Right to Read, which was first adopted in 2010, then updated in 2014 and 2019, positions the “preservation of intellectual freedom for individuals of any age held in jails, prisons, detention facilities, juvenile facilities, immigration facilities, prison work camps, and segregated units within any facility, whether public or private” within the purview of librarians and the public.

Guidelines for services in prisons and jails also exist at the international level. These include the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA) Guidelines for Library Services to Prisoners, now in its 4th edition, and the United Nations (UN) Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. Rule 64 of the UN’s standards states that “Every prison shall have a library for the use of all categories of prisoners, adequately stocked with both recreational and instructional books, and prisoners shall be encouraged to make full use of it.”

Regardless of these professional expectations, standards, and human rights laws, library service levels, expectations, and practices vary from one facility and state to the next, as well as between individuals and departments. This extends to the ways that library services are evaluated in each organization and the fact that the methods by which libraries evaluate their services have shifted over time. Outcomes and impact-based evaluation prioritizes the experiences of library users over input, output, and usage statistics. Project Outcome by the Public Library Association (2016) defines an outcome as “a specific benefit that results from a library program or service.” Impact measurements look specifically at “how people have changed over time and what the significant factors have been in bringing about this change” (Brophy, 2006, p. 58). Impact data is regarded as the “most important indicator of a library’s effectiveness and represents its most meaningful approach to accountability,” yet it is notoriously difficult to capture because it is longitudinal (Connaway, Silipigni and Powell, 2010, pp. 75-76). Until recently, there was a “near-total lack of data” in regards to the impact of prison library services to people who are incarcerated (Rosen, 2020, p. 38).

While some aspects of library services to users for incarcerated people have changed over time, one constant is that there is never enough–resources, as in staff time and budgets, or information about library services to incarcerated people. A review of scholarly literature relating to the subject, conducted by Jane Garner in 2020, showed that most researchers published “only once on the topic rather than building a thematic program of research in the area” over 30 years (p. 241). These shortcomings in research at the intersections of library services and incarceration relate to the need for the PRISM Project, not only in sharing research findings, but also to produce a toolkit to aid other library workers in conducting research in these environments.

Insofar as impact research has been applied at all in the context of library services and incarceration, “critical reasoning skills, self-confidence, self-esteem, empowerment, and changed perspectives,” have been identified as possible impacts, as well as “hope, motivation, social bonds, and mental health” (Warr, 2016, p. 18; Finlay and Bates, 2018; Rosen, 2020). Rosen noted, in 2020, that “the majority of prison library literature remains descriptive in nature and relies more on speculation than empirical claims when describing impact” (p. 38). A 2020 study of library workers who provide services to incarcerated people found that most were not undertaking any formal evaluations and therefore used surrogate measures, such as expressions of gratitude, as substitutes for impact measurement (Jordan-Makely, et al., 2024).

Some researchers have called attention to the emphasis that outcomes and impact research places on rehabilitation and re-entry, a focus which obscures the right to read and positions library services as a privilege, contingent on patrons’ behavior. Escapism, however, centers the patron’s experience and well-being. As identified by Garner (2020), escapism is a feeling known to most readers, but especially important for incarcerated people. Participants in that study said they were “able to experience a form of escape by using their libraries and through reading books supplied by these libraries” (Garner, 2020, p. 5). Garner also conducted a phenomenological study in prison libraries in Australia that grouped the described experiences of library users according to three themes: “library as opportunity for autonomy,” “library as therapy,” and “library role in behaviour management” (2019, p. 346). This research supports the claim that library use in jails and prisons benefits patrons’ well-being and “the whole person.” Participants “attributed the relief of boredom enabled by visiting the library and reading library books to keeping them out of trouble and from committing further crimes, particularly drug use, while in prison” (Garner, 2019, p. 353).

In 2019, a study was conducted in two prisons in Nigeria that aimed at assessing library users’ attitudes towards library services and the effect of the library on their psychological wellbeing. The researchers concluded in the affirmative that “bibliotherapy” was conducive to their research participants’ rehabilitation and showed through survey results that they thought positively about the library. Statistical analysis showed that “self-acceptance, personal growth, and environmental mastery of the construct of psychological wellbeing are indeed related to inmates’ library attitude” (Emasealu, 2019, pp. 85-86).

Escapism, the feeling of disappearing into a riveting story, “being exposed to the knowledge we find in books, and being in the libraries that provide us access to these books,” can help people to step outside of a difficult situation, such as literally being incarcerated, as identified by Garner (2020, p. 5). While this notion of escapism may on the face of it seem at odds with “prosocial behaviors,” disconnecting from unhealthy environments can be a positive choice. Prosocial behaviors have been linked with positive outcomes in social relationships, and psychological health and well-being. The term “prosocial behavior” has been used since at least 1972, when it was used in reference to behaviors that were not antisocial. Prosocial behaviors have been studied in child psychology since 1985 to identify actions intended to help others or create harmony in a group. In these contexts, prosocial behavior has been linked with helping others, altruism, and empathy.

Over time, jails and prisons have altered their orientation towards either punishment or rehabilitation. The move to position libraries as an aid in “reform” dates back to the 1950s (Austin, 2022). Coyle, in 1987, introduced the “public library model,” orienting libraries in jails and prisons towards the ALA Library Bill of Rights. A more recent trend to “normalize” prison settings means creating “opportunities for prison life to mirror normal life as far as possible,” and has been shown to have “genuinely positive impacts on offenders’ behaviour” (Steer, Jewkes, Humphreys, et al. 2016). Thus, present-day prisons are often designed with the intent of creating conditions to engender prosocial behaviors, a term used increasingly in the lexicon of corrections administrators and even in regards to jail and prison staff themselves. “Commitment to the organization apparently is one explanation for why correctional officers perform prosocial acts on the job,” a study concluded, though “no significant correlations were found for achievement, empathy, and concern for others” (Culliver, Sigley, Macneley, 1991, p. 277).

Reading fiction has been linked with empathy, insofar as the reader puts themselves in someone else’s shoes and imagines what they may be feeling (Bal and Veltkamp, 2013). Other studies have connected library use with prosocial outcomes such as feeling connected to one’s community, and well-being (Zickuhr and Purcell, 2014; Blatt, Paloney, Pawelski, et al., 2024). However, low literacy has long been associated with social problems, with some reports citing that up to 75% of people who are incarcerated cannot read (Herrick, 1991; NCES, 1994). It is noted that while “learning to read by itself will not prevent participation in crime, illiteracy may preclude knowledge of the legal system, participation in treatment programs, finishing education, finding employment, and may interfere with establishing good social relationships” (Herrick, 1991).

Further to understanding how libraries engender prosocial behaviors, the PRISM study also set out to learn how libraries in carceral settings could be improved. Staff from CSL were, after all, integral to developing the new Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained, guidelines that are designed to be “comprehensive without becoming prescriptive” (Boyington, et al., 2024). Library services in carceral facilities are notorious for varying from one to the next, as noted by Lehmann in 2003, “from fledgling attempts by a few pioneering individuals or spearheading organizations to establish a few basic services as part of a comprehensive prison education, rehabilitation, and recreation program” (p. 301).

There are many barriers that are known to limit access to information in jails and prisons (Arford, 2013; Austin, 2019, 2022; Day, Leblanc, and Nwokoloh, 2024; Jordan-Makely et al., 2024). A report to the United Nations General Assembly, in 2009, took note of “inadequate prison libraries, or the absence of prison libraries and the absence and confiscation of written and educational material in general,” reported by library users themselves, who mentioned also restrictions and “often a complete absence of, access to and training in information and communication technology and related skills necessary in everyday life” (Munoz, 2009). The many obstacles that impede information access can be taken as opportunities for improvement. Correcting these issues continues the trend to normalize carceral settings. This approach to library services in carceral settings means “providing free access to information and offering the same variety of material as the outside community” and upholding the “values at the heart of librarianship, and [Library and Information Science]: access, democracy, diversity and intellectual freedom” (Austin, et al. 2020, p. 169).

Library workers in carceral settings must follow administrative rules and work around other impediments like their patrons’ strict schedules (Vogel, 2009, Jordan-Makely et al., 2024). As recognized by Finlay, Hanlon, and Bates, a research team who conducted interviews with “global prison library experts,” in 2021, “the quality and extent of library provision is also dependent on prison policy or rules in particular contexts” (2024, p. 3). This team likewise noted the connection between inconsistent library services across prisons and support–or lack thereof–from prison administrators. As described by others who have researched library services in prisons, “This is because the facility’s main priorities are concerned with security and potential security risks, not with the access to information that inmates have” (Day, Leblanc, and Nwokoloh, 2024, para. 13).

Other researchers have also written extensively about censorship as an impediment to library use (Austin, 2023; Day, Leblanc, Nokwoloh, 2024; Eads, 2023; Marquis and Luna, 2023). This includes library workers practicing self-censorship in an attempt to adhere to guidelines in the facilities where they work, or due to their own biases (Arford, 2016; Jordan-Makely, et. al, 2024). As described by Austin, 2023, “passive censorship” is enacted “through limited attention to library services for people who are incarcerated. Lack of staff, books, access to library spaces, or even a physical space for books and information inside facilities is a passive and pervasive form of censorship” (p. 2).

As described in the Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained, jail and prison library collections “should be sufficient to meet the specific information needs of the population but also be broad and responsive enough, through purchases and/or interlibrary loan, to provide a depth of interest and allow for personally directed growth.” On censorship, they offer detailed guidance on navigating this “reality,” but also state clearly:

Censorship should be no greater than necessary to maintain the safety and security of the institution. Carceral facilities must strive to create and execute nonarbitrary, consistent, and clear rules. Decisions should be documented and promptly and transparently communicated to users, publishers, and libraries providing support services. Restriction must be the exception, not the default (Boyington, et al., 2024, p. vii).

Further to guidance regarding censorship and collections, jail and prison administrators and library staff can look to the ALA standards for guidance on creating safe and welcoming spaces for library users. Library staff should be recognized as integral to the library experience, such that they “ensure that collections, programs, and services uphold, and adhere to, ALA standards” (Boyington, et al., 2024, p. xx). Maintaining these professional ideals positions library workers also as “advocates for people in the process of re-entry” (Austin, 2022, p. 143; Ringrose, 2020). Thus, relationships with library staff inside of jails and prisons may build a bridge to library use later on, and help prepare people for re-entry. The Standards for Library Services for the Incarcerated or Detained state:

Incarcerated or detained users should leave their facility with a connection to a public library in their community or their local school district library, as appropriate. Carceral library staff should encourage people exiting the carceral environment to begin or continue a relationship with public libraries and should provide information to individuals about how to access library services once released, including enabling those leaving prison to do so with a library card in hand. Public libraries should coordinate with carceral library staff to provide outreach to recently released people. (Boyington, et al., 2024, p. 5)

This underscores the role library staff may play in regards to library services for incarcerated patrons and prosocial behaviors, and the need for research that documents these connections from the viewpoints of library users who are or were previously incarcerated.

Methods

The scaffolding for the PRISM study was designed through an IMLS-funded planning project that set out to determine the best ways to assess how Colorado prison libraries may help people who are incarcerated to “stay occupied productively and out of trouble while incarcerated and maximize their chances of successful re-entry into the community” (CLiC, 2018).

As is often the case, the PRISM study methods did alter some from the original research proposal, due to changes in administrative staff, partner organizations, and the level of institutional access granted to the research team. Our approach was also informed by our evolving understanding of “prosocial behaviors” and as new research was conducted and published in regards to library services and incarceration. The PRISM Project used grounded theory, which “values the process of continuously developing, refining, and enhancing theory in recognitions that other studies, perspectives, and minds can make to the original effort” (Connaway and Powell, 2010, p. 230). Remerg, a nonprofit that addresses the needs of formerly incarcerated people re-entering the community, was a key player in helping to renegotiate the project and developing the survey instruments and research design.

As people who are incarcerated or were previously incarcerated represent a particularly vulnerable group of research subjects, an independent review board, Heartland IRB, was contracted to help ensure compliance with 45 CFR 46. The survey instrument and research design were approved by Heartland IRB and approved by the Colorado Department of Corrections through their internal processes.

The PRISM study used survey instruments and focus groups to connect with people who are currently incarcerated, and those who were previously incarcerated and have since returned to their homes and communities, to assess what outcomes, if any, could be ascribed to participants’ use of libraries in the Colorado facilities where they are or were incarcerated.

Surveys were distributed inside and outside facilities both on paper and online, with a target sample size of 267 responses from outside and 324 from inside. Our team worked closely with Remerg to revise a survey instrument that was originally created during the grant proposal process. It was intended to be as succinct as possible, and sensitivity readers helped to develop questions that were appropriate for the intended participants. The language that was used in both the focus group questions and surveys was intentionally straightforward, written at a fifth-grade level, and as inviting as possible. Paper surveys were sent to a random selection of currently incarcerated individuals, and the survey was also available online in the prison libraries for anyone interested in taking it. Surveys to people who were formerly incarcerated were made available at parole offices and transitional housing facilities to anyone interested in taking the survey. Findings from these surveys will not be discussed in this white paper. Instead, a secondary paper will be published at a later date to include those findings.

With focus groups, our goal was to reach participants in all Colorado state funded prisons at all custody levels. Inside focus groups participants were randomly selected, then sent invitations to participate. Participation in the outside focus groups was solicited through flyers and word of mouth at parole offices and transitional housing facilities. Each focus group, both inside and outside, had at least two interviewers present: one to take notes and handle the recording, and one to ask questions. The question schedule was created by the original project team, then amended by members of Library Research Service and Remerg.

Focus groups were semi-structured, with a main body of questions and optional, follow-up questions that interviewers asked according to their own discretion, and the flow and content of the group discussion. Interviewers also asked clarifying questions when they deemed it necessary. For the inside groups, snacks were offered as a thank you for participation. While designing our protocol, a formerly incarcerated individual gave us advice to bring fresh fruit and vegetables to the groups, which ended up being incredibly popular. Interviewers from Remerg, our partner organization, traveled to eight locations throughout Colorado to host eight focus groups with formerly incarcerated people, one of which was virtual. Participants were compensated for their time with incentives worth about $20 each.

As soon as interviews were complete, the recordings were sent to Rev for transcription. We then uploaded the data to a recognized qualitative research tool, Dedoose, and began applying codes to transcripts, starting with a list of terms that we expected we may see, which grew and became more defined as our research progressed. Our team kept a codebook which included definitions and notes as to how the terms related to one another. We used a catch-all code, “other,” for noteworthy excerpts that defied our preconceived list. The research team all took part in coding, and met bi-weekly to discuss their experiences and questions. The codebook came to include 23 “parent codes,” some with subheadings (or “child codes”); for example, “Barriers to use,” was a parent code with 15 possible child codes, such as “borrowing time limit,” and “time allowance.” Besides agreeing on definitions, the team also determined parameters for the length of each excerpt. Rather than coding every remark independently, we found that it was more useful to take one “chunk” of conversation at a time, since some participants would riff for a while on a theme or question. Another use of our meeting time was to explore and learn about Dedoose. This was especially true as we were testing for inter-rater reliability, to ensure our agreement in how the codes were applied across the data, from one researcher to the next.

Positionality and Reflexivity Statement

The PRISM Project team was composed of researchers in Colorado and a consultant from Massachusetts, with significant input from advisors at Remerg (a Denver-area re-entry non-profit) and Colorado State Library colleagues who work inside of Colorado prisons and prison libraries. Each of our identities, backgrounds, and worldviews informed how we engaged with participants, interpreted data, and shaped the design of this study. We recognize that our experiences of working in libraries and outsider status relative to the incarcerated community positions us with both limitations and responsibilities. We do not claim to speak for those who are system-impacted, but rather to center and amplify their voices, experiences, and expertise within this research.

Our academic and professional training in Library and Information Science and involvement in prison library programs have informed our understanding of the role of literacy, learning, and access to information in carceral settings.

Throughout the research process, our team has engaged in continuous reflexivity through extensive conversations within our group, as well as with subject matter experts and individuals with lived experience of incarceration. These practices have helped us to challenge our assumptions, identify biases, and remain attentive to the power dynamics inherent in research relationships, particularly when working with a historically marginalized and surveilled population.

We also acknowledge the potential for institutional constraints (e.g., prison policies, surveillance, stigmatization of formerly incarcerated individuals) to influence participants’ willingness or ability to speak openly. We have taken care to create conditions of trust, confidentiality, and respect, and to honor the autonomy of participants throughout our research.

Limitations

A variety of limitations arose throughout our research process. One such limitation was the terminology used by administrators in Colorado prisons, and the lack of definitions and clarity relative to this language. Descriptors that we had planned to use, such as custody levels, were ill-defined, in reality. While custody levels do exist, and shape the experiences of people who participated in the PRISM study, there are many shades of grey within these levels. These data therefore defied the model we had expected to use, and we were unable to draw meaningful comparisons between custody levels and other descriptors that we had initially intended to study. We therefore revisited these data after having analyzed them to the best of our ability to ensure that they matched as closely and realistically as possible. We have included a list of these definitions in the attached Appendix A.

A few limitations arose while conducting focus groups. A few participants of the inside groups told us how the invitation to participate raised suspicion; the wording of the invite, along with official state logos made people wary to participate. The delivery method also caused unease; some invitations were slid under doors during the night, and this made some people uncomfortable. The organizers of the outside focus groups also found it challenging at times to recruit participants.

Another limitation was our inability to include the voice of every person that we heard from in the following report. While we greatly value all of the data and stories that we gathered from our research, and want to center these voices over our own analysis, it is not possible to include every one of the hundreds of excerpts that we collected, or even every one of the quotes that seemed important. While we have placed emphasis throughout this study on genuine representation of people’s words, we have edited the quotes in this paper for clarity. Also of note, some focus group participants said they were unable to speak about their experiences with library services because they had been incarcerated during the COVID pandemic, and therefore had not had the opportunity to visit the library, or to use libraries to their fullest extent.

This study also focuses solely on prisons, and not jails or other detention centers, though these data likely shed light on similar experiences of people incarcerated in those types of facilities as well. Nevertheless, it is necessary to clarify that these focus groups and surveys were limited to this specific context of Colorado prisons (not including privately run facilities).

Even as our data analysis was coming to a close, our own understanding of the patterns emerging from these data continued to grow and come into focus. Thus, it is only in hindsight that we realized we should also have been coding for literacy, non-fiction, studying, and self-regulation, as in when someone separated themselves from a scenario that was challenging or toxic through using the library or reading. We nevertheless discuss these themes in the following analysis.

Focus Group Characteristics

This report focuses on qualitative themes that emerged from participants’ voices during focus groups conducted in Colorado prisons with respect to library services. However, it also includes some quantitative data to describe the participant population and link certain themes to different focus group characteristics. We tracked five characteristics, also called descriptors, across each of the inside focus groups: custody level, number of participants, gender, the library’s collection size, and the number of library staff measured in full-time equivalents (FTEs). For 30 of the 54 focus groups, we also recorded whether participants were in Special Management Groups, such asan Incentive Unit, Management Control, or a Residential Treatment Program. Definitions of these groups can be found in Appendix A.

Custody levels were tracked for all 54 inside focus groups we conducted and categorized into three main groups: Minimum, Medium, and Close. “Minimum” applies to incarcerated individuals with the lowest security restrictions. “Close” refers to those with the highest security restrictions. Out of the 54 focus groups, 24 were designated as Close or Close & Below, 19 as Medium or Medium & Below, and 11 as Minimum or Minimum Restrictive & Below. The term “& Below” indicates that a focus group also included people from less restrictive custody levels.

The number of participants was tracked in 51 focus groups. Whether due to security restrictions, conflicting schedules, or lack of participation, 15 focus groups had only one participant; thus, these were interviews that followed the same question schedule. Most focus groups (16) included two or three participants, while 14 focus groups had four or five participants. Six focus groups consisted of six or seven participants. Seven focus groups were conducted with women’s groups, and 46 were conducted with men. This difference reflects the demographics of the larger prison population, where two facilities are for women, who make up less than ten percent of all incarcerated people in Colorado.

The library spaces and services offered therein varied significantly between facilities. The size of the libraries’ collections ranged from 3,431 to 14,493 items. Each library employs between .2 and four full-time equivalent (FTE) staff. Only one facility has fewer than 1 FTE staff. Nine facilities have one staff FTE, and six facilities have two or close to two staff FTEs. Three facilities have three or four staff FTEs. Custody levels and facility differences were not tracked for the outside focus groups because participants in those groups were not divided based on different facilities or custody levels.

Section One: Outcomes of Prison Library Use

The first goal of this project was to identify outcomes of prison library use. These included outcomes related to developing prosocial behaviors, information literacy and learning skills, and preparing for successful re-entry into the community.

To identify outcomes, we mainly focused on answers to the following questions asked during our focus groups:

- Why do you use your prison library?

- In what ways, if any, has your prison library experience changed how you feel about yourself and/or others?

- Have you ever connected with someone because of the library or because of something you’ve learned in the library?

- Has the opportunity to visit the library changed the way you behave in prison?

- Overall, how do you feel about your prison library?

- Are there any other stories about your experiences with your prison library that you’d like to share?

When focus group participants were asked, “Why do you use your prison library?” the most frequently applied codes to their responses were: “information access,” “escapism,” “collection,” “pass time,” “music,” “self-led learning,” “reading for enjoyment,” and “library services.” The codes “library as an activity,” “mental health,” “library as a place of peace,” and “movies” also appeared but less frequently. This indicates that people use their prison library both for obtaining information and for recreation, such as movies and leisure reading. Additionally, individuals use their prison libraries as sanctuaries of peace and as spaces to work on their mental well-being.

When asked, “In what ways, if any, has your prison library experience changed how you feel about yourself and/or others?” the most common codes identified in the responses were “self-led learning,” “connect with others,” “library services,” “information access,” “mental health,” “positive feelings,” and “prosocial behaviors.” By asking this question, we aimed to understand if library use can foster empathy and self-awareness, two key traits associated with prosocial behavior. A detailed discussion of the specific services used in prison libraries is included in Section Two, but what follows are insights into the outcomes participants identified related to their use of prison libraries.

Prosocial Behaviors

“Prosocial behaviors” was an overarching parent code applied to any excerpts where a person showed an awareness of how they interact with and affect others. Nested within “prosocial behaviors,” there were more specific child codes: “agreement,” “connect with others,” “democracy,” “donate time/resources,” “empathy,” “expressing appreciation,” “helping others,” “leadership,” “respect for others/property,” “role modeling,” “social norms/normalization,” “turn-taking (within focus groups),” and “work with others.” All these child codes appeared in our data. Many of the prosocial behavior codes, although applied to both men’s and women’s focus groups, were identified at a higher rate in women’s focus groups than in men’s. These included “empathy,” “helping others,” “expressing appreciation,” and “respect for others/property.” The men’s focus groups, on the other hand, discussed the prosocial behaviors “role modeling,” “donate time/resources,” and “democracy,” more frequently than women.

Prosocial behavior codes could also be associated with different custody levels. “Expressing appreciation” and “respect for others/property” were observed more frequently in focus groups conducted with people in Minimum and Minimum Restrictive & Below custody levels. The prosocial behavior code “work with others” was identified at the highest rate in focus groups of people in Close and Close & Below custody levels, two groups with very limited social interaction on a daily basis.

Looking at inside groups, the least frequently identified prosocial child code was “democracy,” which appeared in only eight transcripts. The most frequently identified prosocial child code was “connect with others.” Below, we examine four of the prosocial behaviors that may result from prison library use: “connect with others” (in 53 of the 62 inside and outside transcripts), “respect for others/property” (in 35 of the 62 inside and outside transcripts), “expressing appreciation” (in 33 of the 62 inside and outside transcripts), and “helping others” (in 26 of the 62 inside and outside transcripts). Occasionally, participants used the term “prosocial” themselves to describe their time in the library, with one focus group participant who was formerly incarcerated stating, “[The] library is a very prosocial environment for prison, probably one of the most.”

Within the eight focus groups conducted on the outside, connection with others and “respect for others or property” were found in all but one transcript. “Agreement” was also noted in seven transcripts, which is a much higher rate than in the inside transcripts. Conversely, “helping others” was less common in the outside transcripts compared to the inside transcripts.

Connection With Others

Connecting with others is a strong marker of prosocial behaviors. It was identified in 46 of the 54 focus groups conducted with currently incarcerated people and seven of the eight outside focus groups. Only a few of the excerpts identified came from participants saying they had not connected with someone because of the library or something they learned there. Most mentions of connecting with others were positive, such as the example, “Sometimes you can read something and it would, once you bring it up to somebody, they relate to that same thing that’s in the book and that’s what creates a friendship bond . . .” The code “prosocial behavior ” was often applied in response to the question, “Have you ever connected with someone because of the library or because of something you’ve learned in the library?” as in the following example:

Speaker 2: Especially in lockup. I came across a new author . . . So I pass that on to my next door neighbor and we read a few of his books and we have insight about the books.

Interviewer: Oh, cool.

Speaker 2: And exchange of what we feel about the book. So yes, I have relayed with people about books.

Interviewer: Okay. Yeah, it’s a little book club with you and your neighbor.

Speaker 2: Man. I mean, 23 hours locked down, you got to vent so we can talk like this. Instead of talking about something negative, talk about something positive.

In response to this question, one participant even used the term “prosocial,” and then unpacked the term:

Speaker 5: . . . because it creates a prosocial environment, you know what I mean? You start a book and everybody’s in here doing it.

Interviewer: What do you mean by prosocial?

Speaker 5: Like everyone’s sitting here interacting with each other, even people you don’t normally talk to.

When reflecting on their time in the prison library, one participant in the outside focus groups referred to the library space itself as a reason they were able to communicate and connect with others:

A common ground type thing. That’s what I found in the library too. I mean when you go to the library and there’s guys in there, man, it’s more social than anywhere else. You can go to this. “What’s going on man? What you reading? Hey dude, I’m reading this. What’s going on with this?”. . . the library is like common ground and you can always go to somebody and say, “man, what is that that you was reading? Because you look real interested” he said, “it’s a good book, man, I’ll show you where it’s at.” And everybody, it’s just neutral ground. There’s no funk in the library.

Another focus group participant reflected on how the library offers a space to overcome social barriers:

Speaker [?]: Yeah, the library’s not political.

Speaker 5: Yeah, it’s not. It’s just you only got one. One room.

Speaker 3: When you’re in a library, you don’t get to. . . I’m not going to kick it with the whites or Blacks or Mexicans. It’s just all. And it helps you break down stereotyping. Because he could be super involved in passion novels and he can be like hardcore gangster novels.

These types of interactions function as a way to find new materials and relate to others, as shown in the interactions described by this participant:

I’ve noticed too like. . . Me and this other girl, we had a similar liking of the type of books and the way they’re written. So it was always fun to see what books she was reading at the moment. And then every time I would find a book in the library, I would go and show her, look at how good this book looks. And so being able to know that this person enjoys that specific type of writing and type of fiction or genre, that the book is fun to connect with someone on that or when other people enjoy that type of stuff too. It’s a thing that you guys can connect on that’s a healthy thing.

When talking about their interactions with the people around them, another focus group participant said, “We get together and remind each other it’s library day.” There were many excerpts that highlight the link between connecting with others and prosocial behaviors:

Yeah, I feel like it’s connection when we all sit together and do something in here. Because up in the unit, we’re all just doing our own thing or whatever. So when we sit down and watch a movie or ask, “Hey, what book are you reading?” It kind of brings us closer together.

Coming here and then when you’re new and being in here with people from your pod, sometimes you find out that they like reading the same books as you; so just being able to form connections just by seeing what other people are reading, I think it’s super huge to be able to do that, to feel better and to feel more connected with others and with yourself.

One focus group participant stated, “It’s a meeting place and I like to be, I like to associate with people who are interested in becoming more, improving themselves.” Another participant also spoke positively about the people they were able to connect with in the library:

[. . .] when I first came to prison, I was a hard-headed kid who clearly made these bad decisions and then compounded them bad decisions by making more bad decisions. So when I started coming to the library and I started getting more into books, it’s different when you come to the library because there’s a different element of person that hangs out in the library and reads books compared to the ones that are in the pod making trouble and picking fights with other people. So getting to hang around with people who are a little more into books and a mellow lifestyle . . . You start to get a different perspective on life and you start trying to change your own ways. So that’s how it’s helped me. I got to come to the library and meet a different kind of person and see things in him that I like to try to emulate.

Some respondents described how the library or something they had read there helped them empathize with others and communicate more effectively.

[. . .] the spiritual books and stuff . . . I kind of be up in them, too. Because it kind of gets you spiritual balance with yourself . . . It kind of teach you other people energy. So if you feed off another person’s energy, so really you got to humble yourself to overcome any situation that you’re facing nowadays, no matter what it may be. And talk about it in a nice tone and be sincere about it. So that’s what I’ve been learning in the library, self-teaching and learning all the other folks’ actions. And know how to deal with people with problems, that don’t know how to deal with their problems. And tell them how you feel about situations. So that’s the little remedy I got up out of the hood.

Someone else explained how sharing materials in the library helped them to tackle difficult subjects with loved ones:

I gave my lady a title of a book for her to check out because she wanted to understand more. I told her, “This isn’t going to be an easy process because a lot of people can’t handle being with somebody that’s going through a transition. This is a book that can help you to understand a little bit more of what body dysmorphia is and what I’m going through in my mind and what a struggle it is going through this process and having to correct people constantly and feeling down about myself.” I go through up and downs with emotions a lot. My body’s trying to level out with the testosterone and with the estrogen in it. There’s a book in there that I told her to read and she’s checking it out and it’s helping her a little bit to understand more I guess. I want to be able to tell my mom about it, but that’s one person I’m kind of scared to come out to. But hopefully when I get out I can send her that book and have her read it. I don’t know.

Directly in response to the question, “Have you ever connected with someone because of the library or because of something you’ve learned in the library?” the code “connect with others” was applied in 28 of 54 inside transcripts and five of eight outside transcripts. Besides connecting with others in the facility, library use and reading helped some focus group participants stay in touch with family. For example, one participant answered, “Just to interact with your kids just on some books to get them involved in books. Or y’all could just read the same book. I think that’d be pretty cool.” In another focus group, a participant explained, “I read books in here and I’ll go and hop on the phone with a family member and I’ll just tell them what I’m reading, with that kind of converse on that.”

One focus group participant shared that the library helped them connect to their family by learning about their interests: “my daughter plays violin, so I would like to learn how to read music a little bit better so that maybe I can pick up an instrument with her.” And another participant shared their excitement for Family Day, when they will perform the ukulele skills they learned at the library. Not only are these both instances of prosocial behavior through connecting with family, but they also both demonstrate how people use the library to learn new skills.

Besides staying connected with family, participants also discussed how they use the library to connect to the wider world. One respondent said, “It helps connect you to the outside world, I guess, through reading and watching movies, or listening to DVDs that would otherwise be unavailable to us here in this prison setting.”

Library use and reading also helped some participants improve their own communication styles:

Like learn how to talk to people, be like, “Hey bro, I feel like can I talk to you for a minute?” Don’t make him feel like that I’m kind of like, if I come to him, like, “Hey bro, I need to . . .” That’ll make him throw his tactic mode on. You know what I’m saying? Like I’m trying to attack him. But if you come with some, “Hey bro, can I talk to you for a minute, whenever you have time?” You know what I’m saying? He be like, “Okay, I got you.”

In another excerpt, participants described how it expanded their vocabulary:

Speaker [?]: Another way it helps is it’s helped me expand more on . . . I’m going to be honest, it’s helped me expand more on my vocabulary. I didn’t have quite the best vocabulary. Consisted of a lot of slang.

Speaker 5: Or know how to talk to people. That’s how I’ve been, too.

Speaker 4: Throughout reading books in the library, I’ve been able to expand my vocabulary and be able to learn how to talk to people in certain ways. And not approach them, because if I come at someone, I’m like, “Aye,” and I use any type of slander that I may think is okay, they might think is wrong and it might not be the right way. This also helped me with my vocabulary, because if I’m sitting in a job interview, if I say the N word every other word, they’re going to be like, “Yeah, you’re definitely not getting hired.” So it’s kind of helpful in that way, too.

The excerpt above illustrates how improving one’s communication skills can assist with re-entry into society outside of prison. Another participant described how using the library to stay connected and communicate helped them prepare for re-entry after their release:

For me, it’s really helped me understand that I can communicate with the people out there. I used to think that there was a huge barrier between those guys out there and me in here because none of the stuff that I was doing in here had anything to do with what they were doing out there. But the information that we could share back and forth about businesses, like I said, what I’ve [inaudible] and businesses and taxes and stuff like that, it’s really actually between me and my cousin, it has allowed us to build a really good foundational relationship of this is what we’re going to do when I get out there and what we’re going to do when I actually do get to that world. So it opens up a line of communication just by having knowledge and I love it.

Working in the library also helped a participant explore a new career path and build a professional network. They secured long-term, stable employment with an organization that provides prison programming.

Connecting with others can also be passive, as described here:

Coming to the library, watching different people use different music and how it makes them feel and how you see how this guy who is kind of depressed goes into a completely different state. Another guy is reading a book and you see their whole vibrance change. And then it makes you think completely different for that person. Instead of just being like, “Oh they need some help that I can’t give them.” But then the library is giving it to them because they’re getting the help that they need through their therapy, through music or through just being able to get their mind off of whatever it is with that reading. And just to know that there’s things out there that they can get help from. And that not to necessarily feel bad for them because they might just be down waiting for that next time to get that uplifting joy.

Multiple focus group participants explained how they gained a better understanding of people after observing them in the library.

Speaker 5: A positive thing about the library to me, I mean you get to see different people. You learn the different people who observe different people. Like you say you might be in the library and one of the hardest guys on the yard or [inaudible] hardest guy on the yard, he come over and he’s searching for a book on Dungeons and Dragons or some kind of game that you wouldn’t see him engaged in. So it gives you an outlook on how people react away from their general crowds.

So I mean, I’ve been to the library and I used to have a client that worked in the library, so I would have to go over to the library to pick my client up and I would see guys in there that I would see on the yard walking around with their chest poked out and this and that there. But they over here read the book on fairies and dragons and this and that. Then I’m like, okay, wouldn’t expect that. But it teaches you. It also lets you interact with other people and get to know people outside of their environment because it seems like they let their guard down when they’re doing their thing, they’re in their moment.

Speaker 1: Their facade is broken.

Seeing what people are actually interested in. You think, oh, this was just a hardheaded knucklehead or something like that, then you see him picking up the dictionary and he’s trying to learn something. Or he’s picking up something that’s trying to benefit him in some type of way. Or even myself for example, I’ll come in here and I’ll be like, oh, I’m just going to come walk around. I want to get out of the pod for a while. But then I find myself getting indulged into some fairytale land or something like that. I mean that’s a big thing right there.

While using the prison library, connections could also occur with library staff. One participant stated, “I used to connect with a lot of the librarians.” And another focus group member described their connection with library staff: “I think I have a good connection with the librarians. They’re pretty helpful. And then they won’t treat you like you’re an inmate really. Some people that work here, they’ll treat you like you’re just an inmate and that they’re better, but the librarians aren’t really like that.” Another participant shared:

It really just brought us together with the workers or even the librarian. She’s told me about a couple books and I’ve gone and found them. And it just kind of opens up that barrier, because we tend to shut down and keep within ourselves in here because it’s easier that way. So being able to have some type of common ground has helped.

We also heard from library workers who described their experiences as library clerks, which often included stories of connecting with library users. For example, one participant said, “There’s been a few times that since I’ve started working here where I’ve gotten to meet people in different pods and find out we have certain stuff in common. But I wouldn’t have known that before because I wouldn’t have taken the time out of my day to talk to them if I didn’t have to, being in here.” Over and over again we heard how prison libraries help people open up:

It makes me a little more sociable. I’m not . . . from the beginning, I was a real sociable person and then as I got older, I kind of closed off. But whenever you come here, there’s people just sitting around reading or listening to music or I haven’t really had a bad experience with it. There’s always the librarians that are walking around, “Can I help you with anything?” It helps me be a little more sociable.

Respect for Others/Property

Throughout focus groups respect was shown by participants for the library space, the materials in the library, and people in the library, including staff. The codes “respect for others/property,” “expressing appreciation,” and “social norms/normalization” overlapped quite a bit. In addition to showing respect, participants voiced the significance of being treated with respect in the library. For example, one person explained:

And I remember the first time I came into the library here, I grabbed the Poison series and I was checking it out and the librarian walked up to me. And she was like, “Oh, I love that series. What do you think of it?” And it kind of threw me off because that’s not the way I’m used to interacting with authority from where I came from. And so I was skeptical and I was nervous the first few times that she talked to me. But it kept on like that. The librarian kept, “Oh I love that series too.”

Another participant emphasized why it is important to be treated with respect. This same participant, who earlier stated, “libraries are institutions that help dignify us,” told interviewers:

[. . .] there should be some legislation that every prison, any institution like this should have a library. I mean, it would be in the best interest of society, recidivism rates would come down, education, everything. But we don’t live in that type of world, unfortunately. Like I mentioned, you have resistance and I’m pretty sure that’s what you’re up against and that’s what you’re trying to prove. But it’s not easy and to that respect I appreciate your guys’ effort. Libraries are in every sense, they’re just an essential part of humanity. You come to read, you come to learn, you escape this environment, everything . . . It’s just, why would you even have to present that as an argument? The same could be said for recreation. It’s there for a reason to help us release stress and whatnot. Those are positive things. You shouldn’t take that away from inmates. You should give them more of that. You should give them more education and give them more library. You should give them more recreation. They should treat us like we’re human beings.

“Behavior Modification” and “library as a place of peace” were also applied multiple times alongside “respect for others/property.” Participants described how people behaved differently in the library because of their respect for the space and the importance of keeping peace within it. This reoccurring sentiment is summed up well by the following excerpt:

And it’s crazy that even though it is super wild in the units or anything, even the wildest unit, if they come in here, everyone knows that it’s the library, so it’s time to be quiet. So it’s just really beautiful because everyone knows that you be quiet in the library, and it’s like a sacred space almost. So it’s just really nice to see that even though we are in prison, everyone has that shared respect and acknowledgement that this is everyone’s quiet space.

Expressing Appreciation

“Expressing appreciation” was a prosocial behavior observed when people voiced their gratitude or thankfulness for any aspect of the library or the experience they were currently having. People often expressed appreciation for the prison library and its staff: “I’m glad we have a library. A lot of places ain’t got access to library. And we can always complain it could be worse, we can always complain it could be better. So I’m thankful that we have people in the library that do try to help. I’m grateful for that.” Another participant in the outside focus groups stated:

I just feel thankful. Even though the system’s flawed, and it might not be perfect, but it is an opportunity, especially facilities where you’re locked down 3, 4, 5, 6 weeks at a time, and you have the opportunity to go to a library and get something to read is better than not having anything at all. So, I’m just thankful that there actually is a library there that we can access at some point in time.

In 15 of 54 inside transcripts and three of eight outside transcripts, “Expressing appreciation” was applied in conjunction with “Staff Assistance” or “Staff,” or both. One participant said:

She’s [the librarian] amazing, helpful. She’s very knowledgeable. She knows where things is and she’s well-read. So she’s able to point you in the right direction. And if you’re stuck on where you kind of go next, she knows where to go. So I think that’s really positive.

People also acknowledged that the librarians are not always in control of the barriers to library use: “[Redacted] used to be a librarian. She’s not no more. She was great. They’re all respectful. They work hard for us when they can. Sometimes you go on lockdown and stuff like that for different situation, and they can’t get to us, but that’s not their fault.” Another participant who worked in the library described how one librarian was able to make a significant impact in a short period of time:

And what she did in this library in two months, three months was amazing. She took 1,500 books off that were missing or lost that no one had gotten around to in years. We went over to that new numbering system . . . We got in, I don’t know, 2,000 new books and we were all working double time and just she got this place squared away in a heartbeat. And then she got promoted up front so we lost her.

Focus group participants expressed appreciation for professional librarians as well as for currently incarcerated people who work in the library. One participant said, “The guys that work here are great, too. They’re very helpful. He works here. And I know when I do come through, I’ve been in classes with him here at this facility, the other courses and very helpful. You know, never a negative experience coming in here. So that’s good.” Focus groups often ended with participants thanking interviewers or expressing appreciation for the project, such as, “Well I think what you guys are doing here today is very important. I would like to thank you guys.”

Helping Others

“Helping others” was a prosocial behavior observed in 23 of the 54 inside transcripts and three of the eight outside transcripts. People most often mentioned helping others when asked, “Have you ever connected with someone because of the library or because of something you’ve learned in the library?” and “In what ways, if any, has your prison library experience changed how you feel about yourself and/or others?” They described helping others access materials within the library or the library space itself:

Speaker 3: Usually the girls would just ask someone to go for them, or if you’re close to people, you ask them if we could go instead of them this time, and we’ll rent a book for them or whatever. You know what I mean? If they want a book, we’ll get them one, and then we’ll be able to go.

Interviewer: So there’s some cooperation there?

Speaker 3: Yeah. Communication between us.

People also spoke of helping each other get through tough situations by reading books:

When something bad happens here, like someone gets denied parole or something, I have books and I offer them to them. I’m like, “Hey, this is a great book, you’re going to love this.” And it keeps people’s minds off of things. And it really helps. Like she said, a lot of inmates here have mental health issues, so escapism, even uplifting stories, things that they can empathize with. It all works out great because we need that and we need that connection with other people, just talking about it.

One focus group participant, who worked as an Offender Care Assistant, explained how the library supported patients with dementia:

I mean . . . we deal specifically with the dementia patients. This old guy that we lost last year, would love just coming up here and putting on the headphones. And music seems to trigger a lot of happy memories with our guys, so we try to bring them, show them some old pictures, or let them listen to music. And it’s just a good, relaxing place.

People also said that the library is a space where they can always find help, whether from librarians or staff who are also incarcerated. One participant described receiving help with accessing technology:

You get assistance here, every problem that I’ve had, somebody help me, even if I wasn’t able to work the computer, what they have in this library, the computer access to that, somebody always came and helped me with that.

One person working as a clerk in the library explained that helping others creates a unique environment in prison that is important:

I used to work in the library. It was my second job here and I worked in here for over a year. And it just was great. The environment was great – it not feeling like prison. And so then also being able to be a clerk, you were able to help people, and just in this environment, that’s not always what we can do. And so just being around, that was super important to me and my incarceration.

Focus groups showed that the library is a place where people can help each other in meaningful ways. Opportunities to help others were not always available outside the library. Both those giving help and those receiving help seemed to benefit from these interactions.

Behavior Modification

In approximately three out of every four focus groups (conducted with both currently and formerly incarcerated people) people acknowledged that their behavior changed because of the opportunity to visit the library. Although not categorized with specific codes, several groupings of behavior change were identified. These included “staying out of trouble” and instances where the library positively impacted people’s perspectives, mood, or thinking, leading to different behaviors. Here is an example of a respondent discussing how the library helped them to “stay out of trouble”:

It gives me something to look forward to. It gives me the incentive to stay out of trouble, because if I get in trouble, then I’m not going to be able to come to the library or do anything else, go to rec or anything. I guess, more or less it has helped me focus on things that I want and things that I need. Because the library, just because is small, it does help you with a lot of stuff that you need. So yeah, it has changed my thought process on certain things for sure.

One participant described ways that library staff offered incentives for good behavior:

So the librarian there started a program that if you were cool, if you exhibited positive behavior while in ad seg [administrative segregation] for that month prior to that, she would allow you to have books sent in to donate to the library. She would let you read them first before they processed them into the library system. Or actually, they would be processed in, and then she would allow you to read them. So yeah, that was kind of the Pavlov dog type of training there.

The following excerpts exemplify a shift in people’s perspectives which then influenced behavior:

I think it does make a difference with us because say, coming to the library, being able to look at books, being able to read or listen to music does affect people’s behaviors because I’ve noticed after the library, everybody’s in a good mood and relaxed, and they come back to the pod, and they’re behaving. So, it plays a big impact on people when they get a chance to step out of the pod and come down here. So the libraries do help.

I would say maybe like he said, that it does help you decompress. Sometimes, just being in the pod is too much sometimes. You just want to come in here, you do your own thing. You feel more, I guess, meditative. When you go back to the pod, you’re not on that same bad vibe anymore.

One focus group talked about how being treated with respect by library staff could influence behavior:

Speaker 5: I think it just changes your perception when people treat you different instead of you’re an inmate and being disrespectful with you and . . . When you sit there and communicate with a person, I think it makes you think about life differently, especially when you’ve done a lot of time. You know what I mean? . . . And that’s what I noticed about some of the facilities that I’ve been at. The staff members that worked in there are usually nice and not the whole [inaudible] closed off. I think when you close people off and you make them want to treat us like we’re scum, people start acting a certain way. You know what I mean?

Speaker 2: Yeah, they don’t look down now on you. They treat you like a normal person. That makes you feel more comfortable, more open than [inaudible].

In a few responses to the question “Has the opportunity to visit the library changed the way you behave in prison?” the codes “escapism,” “library as a place of peace,” and “atmosphere” were identified concurrently which suggests that the relief provided by the prison library contributed to behavior changes:

It has definitely changed me because it just calms me down a lot more, especially when people in the pod like to pick on us and everything. It’s like I said, a getaway to another environment just to calm down, listen to music, do something productive, read a book in a silent place without trying to read in the nighttime, and then not be reading in the pod that much because everything’s loud and annoying people.