Intro

Can I trust this information? We use information constantly to learn, make decisions, and form opinions. Every day library staff in every setting strive to teach people how to find the information they need and how to identify trustworthy sources. But what is trustworthy? How can you tell? What about when sources contradict each other? What characteristics distinguish sources from each other?

Who

As a former information literacy librarian at a university, these questions haunted me when I was teaching. I was lucky to meet two librarians at the University of Denver (DU) who shared a passion for this topic: Carrie Forbes, the Associate Dean for Student and Scholar Services, and Bridget Farrell, the Coordinator of Library Instruction & Reference Services. Together, we designed a research project to learn more about how students thought about “authority as constructed and contextual,” as defined in the ACRL information literacy framework.

Why

As instructors, we had seen students struggle with the concept of different types of authority being more or less relevant in different contexts. Often they had the idea that “scholarly articles = good” and “news articles = bad.” Given the overwhelming complexity of evaluating information in our world, we wanted to help students evaluate authority in a more nuanced and complex way. We hoped that by understanding the perceptions and skills of students, particularly first year students, we could better teach them the skills they need to sort through it all.

How: Data collection

We designed a lesson that included definitions of authority and gave examples of types of information students could find about authors, like finding their LinkedIn page. The goal here was not to give students an extensive, thorough lesson on how to evaluate authority. We wanted to give them enough information to complete the assignment and show us what they already knew and thought. Essentially, this was a pre-assessment. (The slides for the lesson are available for your reference. Please contact Carrie Forbes if you would like to use them.)

The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board at DU. Thanks to a partnership with the University Writing Program, we were able to collect data during library instruction sessions in first year writing courses. During the session, students were asked to find a news article and scholarly article on the same topic and then report on different elements of authority for both articles: the author’s current job title, their education, how they back up their points (quotes, references, etc.), and what communities they belong to that could inform their perspective. Then we asked them to use all of these elements to come to a conclusion about each article’s credibility, and, finally, to compare the two articles using the information that they had found. We collected their responses using a Qualtrics online form. (The form is available for your references. Please contact Carrie Forbes if you would like to use it.)

Thanks to the hard work of Carrie and Bridget, the generous participation of eight DU librarians, 13 writing faculty, and over 200 students who agreed to participate after reviewing our informed consent process, we were able to collect 175 complete student responses that we coded using a rubric we created. Before the project was over, we added two new coders, Leah Breevoort, the research assistant here at LRS, and Kristen Whitson, a volunteer from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who both contributed great insight and many, many hours of coding. Carrie and Bridget are working on analyzing the data set in a different way, so keep your eyes out for their findings as well.

Takeaway 1: First year students need significant support assessing authority

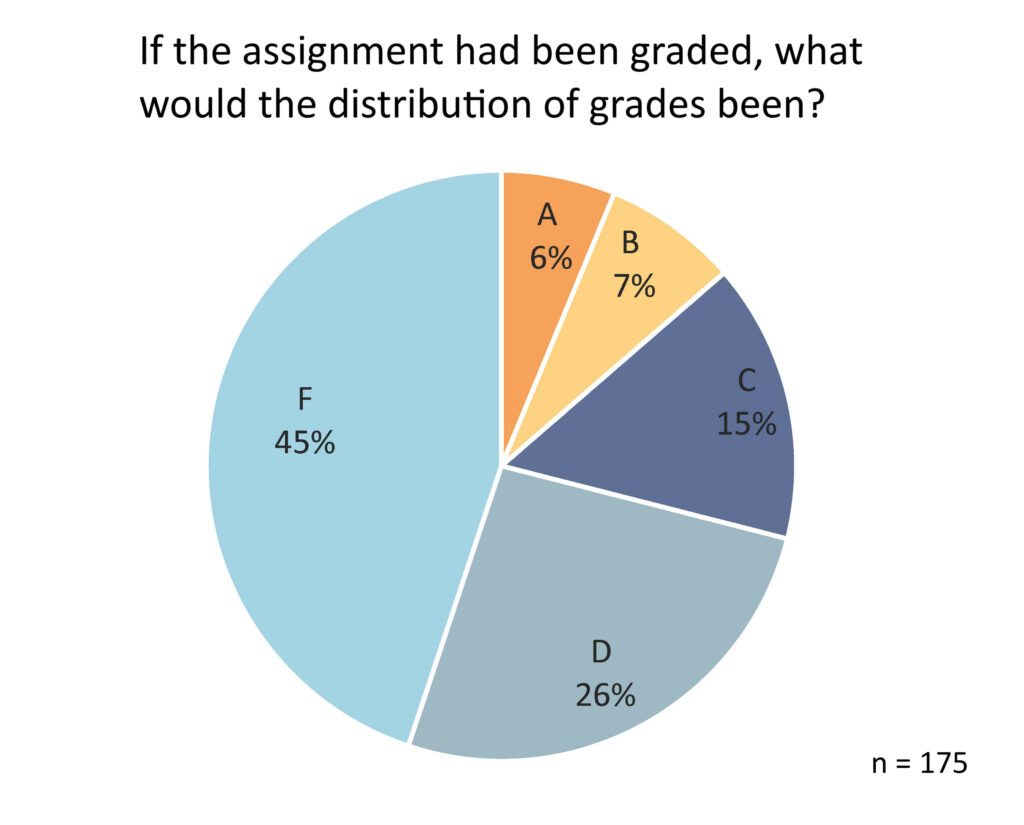

This was a pre-assessment and the classroom instruction was designed to give students just enough knowledge to complete the assignment and demonstrate their current understanding of the topics. If this had been graded, almost half (45%) of the students would have failed the assignment. Most instruction librarians get 45 minutes to an hour once a semester or quarter with a group of students and are typically expected to cover searching for articles and using databases–at the very least. That leaves them very little time to cover authority in depth.

Recommendations

- The data demonstrates that students need significant support with these concepts. Students’ ability to think critically about information impacts their ability to be successful in a post-secondary environment. Academic librarians could use this data to demonstrate the need for more instruction dedicated to this topic.

- School librarians could consider how to address these topics in ways appropriate to students in middle school and up. While a strong understanding of authority may not be as vital to academic success prior to post-secondary education, the more exposure students have to these ideas the more understanding they can build over time.

- Public libraries could consider if they want to offer information literacy workshops for the general public that address these skills. Interest levels would depend on the specific community context, but these skills are important for the general population to navigate the world we live in.

Takeaway 2: First year students especially need support understanding how communities and identities impact authority in different ways.

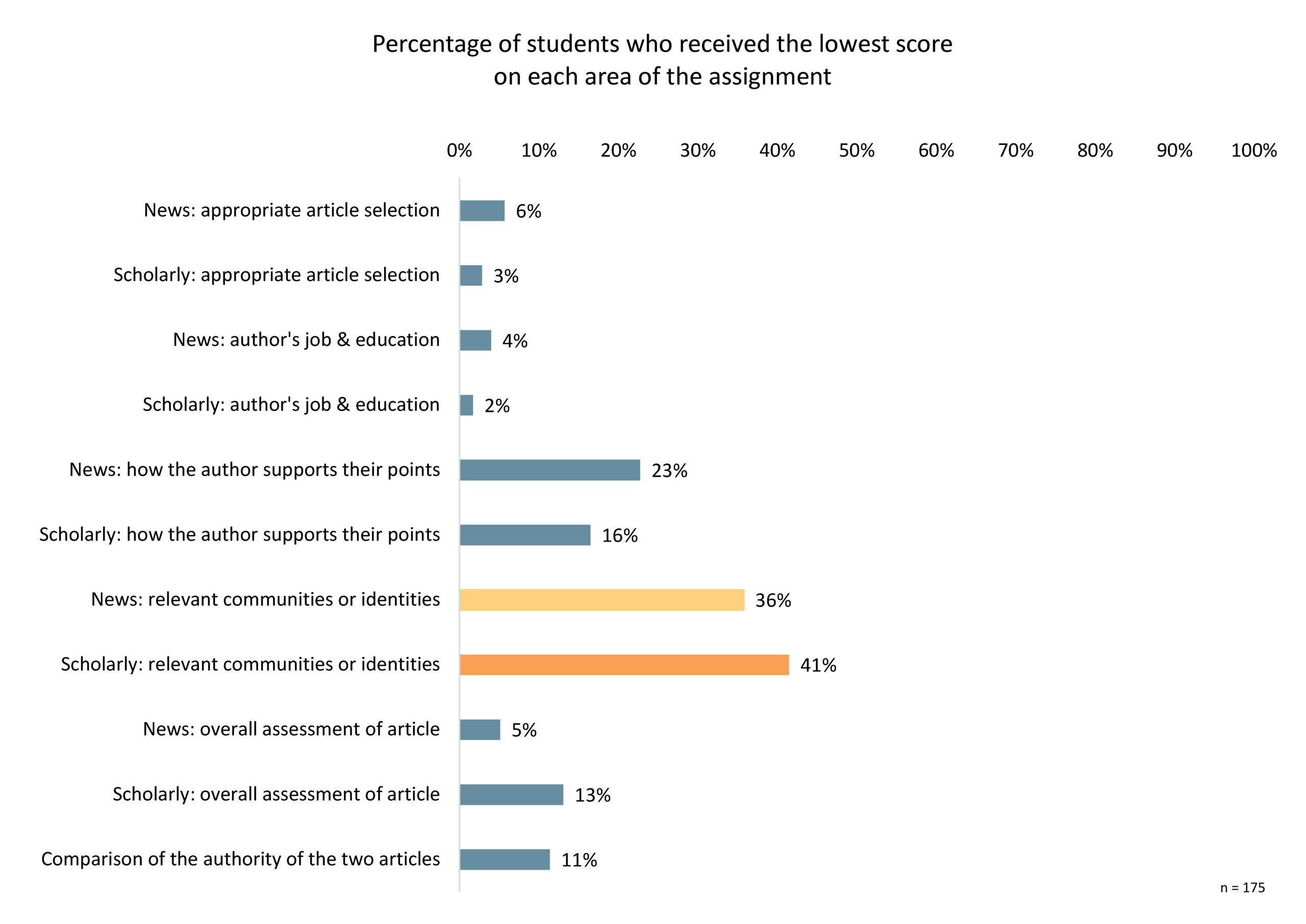

On the questions about communities for both the news and scholarly articles, more than a third of students scored at the lowest level: 35% for news and 41% for scholarly. This is the language from the question:

Are there any communities the author identifies with? Are those communities relevant to the topic they are writing about? If so, which ones? How is that relevant to their point of view? For example, if the author is writing about nuclear weapons, did they serve in the military? If so, the author’s military experience might mean they have direct experience with policies related to nuclear weapons.

Asking students to think about communities and identities is asking them to think about bias and perspective. This is challenging for many reasons. First, it is difficult to define what is an identity or community that is relevant to a specific topic and to distinguish between professional identities and personal identities. For many scholarly authors, there is little publicly available information about them other than their professional memberships. As Kristen observed: “it was really common for students to list other elements of authority (work experience, education) in the community fields.”

Asking students to think about communities and identities is asking them to think about bias and perspective. This is challenging for many reasons. First, it is difficult to define what is an identity or community that is relevant to a specific topic and to distinguish between professional identities and personal identities. For many scholarly authors, there is little publicly available information about them other than their professional memberships. As Kristen observed: “it was really common for students to list other elements of authority (work experience, education) in the community fields.”

Second, how can you teach students to look for relevant communities and identities without making problematic assumptions? For example, one student did an excellent job of investigating communities and identities working with an article entitled Brain drain: Do economic conditions “push” doctors out of developing countries? The student identified that the author was trained as both an economist and a medical doctor and had unique insight in the topic because of these two backgrounds.

What the student missed, though, was that the author received their medical degree from a university in a developing country and how this may give them unique insight into doctors’ experiences in that context. In this example, the author’s LinkedIn made it clear that they had lived in a developing country. In another instance, however, a student thought that an article about the President of Poland was written by the President of Poland–which was inaccurate and led to a chain of erroneous assumptions. In another case, a student thought an article by Elizabeth Holmes was written by Elizabeth Holmes of the Theranos scandal. While it seems positive to push students to think more deeply about perspectives and personal experiences, it has to be done carefully and based on concrete information instead of assumptions.

Third, if librarians teach directly about using identities and communities in evaluating information sources, they need to address the complex relationships between personal experience, identities, communities, bias, and insight. Everyone’s experiences and identities give them particular insight and expertise as well as blind spots and prejudices. As put by the researcher Jennifer Eberhardt, “Bias is a natural byproduct of the way our brains work.”

Recommendations

- There are no easy answers here. Addressing identities, communities, bias, and insight needs to be done thoughtfully, but that doesn’t make it any less urgent to teach this skill.

- For academic librarians, this is an excellent place to collaborate with faculty about how they are addressing these issues in their course content. For public librarians, supporting conversations around how different identities and communities impact perspectives could be a good way to increase people’s familiarity with this concept. Similarly, for school librarians, discussing perspective in the context of book groups and discussions could be a valuable way to introduce this idea.

Takeaway 3: An article with strong bias looked credible even when a student evaluated it thoroughly.

When we encountered one particular article, all of the coders noticed the tone because of words and phrases like “persecution,” “slaughtered,” “murderer,” “beaten senseless,” and “sadistically.” (If you want to read the article, you can contact the research team: some of the language and content may be triggering or upsetting.) This led us to wonder if it was a news source, and look more into the organization where it was published. We found was it was identified as an Islamophobic source by the Bridge Initiative at Georgetown University.

The student who evaluated this article completed the assignment thoroughly – finding the author’s education, noting their relevant communities and identities, and identifying that quotes were included to back up statements. The author did have a relevant education and used quotes. This example illustrates just how fuzzy the line can become between a source that has authority and one that should be considered with skepticism. It is a subjective, nuanced process.

This article also revealed some of the weaknesses in our assignment. We didn’t ask students to look at the publication itself, like if it has an editorial board, or to consider the tone and language used. These both would have been helpful in this case. As librarians, we have so much more context and background knowledge to aid us in evaluating sources. How can we train students in some of these strategies that we may not even be very aware we are using?

Recommendations:

- It would be helpful to add both noticing tone and investigating the publication to the criteria we teach students to use for evaluating authority.

- Creating the rubric forced us to be meta-cognitive about the skills and background knowledge we were using to evaluate sources. This is probably a valuable conversation for all types of librarians and library staff to have before and while teaching these skills to others.

- The line between credible news and the rest of the internet is growing fuzzier and fuzzier and is probably going to keep changing. We struggled to define what a news article is throughout this process. It seems important to be transparent about the messiness of evaluating authority when teaching these skills.

Takeaway 4: Many students saw journalists as inherently unprofessional and lacking skills.

We were coding on the rubric more so than doing a thematic qualitative analysis, so we don’t know how many times students wrote about journalists not being credible in their comparison between the news and scholarly article. In our final round of coding, however, Leah, Kristen, and I were all surprised by how frequently we saw this explanation. When we did see this, the student’s reasoning was often that the author’s status as a journalist was a barrier to being a credible source, like the article could not be credible because the author was a journalist. Sometimes students had this perspective when the author was a journalist working for a generally reputable publication, like the news section of the Wall Street Journal.

Recommendations

- This is definitely an area that warrants further investigation.

- Being aware of this perspective, library staff leading instruction could facilitate conversations around journalists and journalism to better understand this perspective.

How: Data analysis

It turns out that the data collection, which took place in winter and spring 2018, was the easy part. We planned to code the data using a scoring rubric. We wanted to make sure that the rubric was reliable, meaning that if different coders used it (or anyone else, including you!) it would yield similar results.

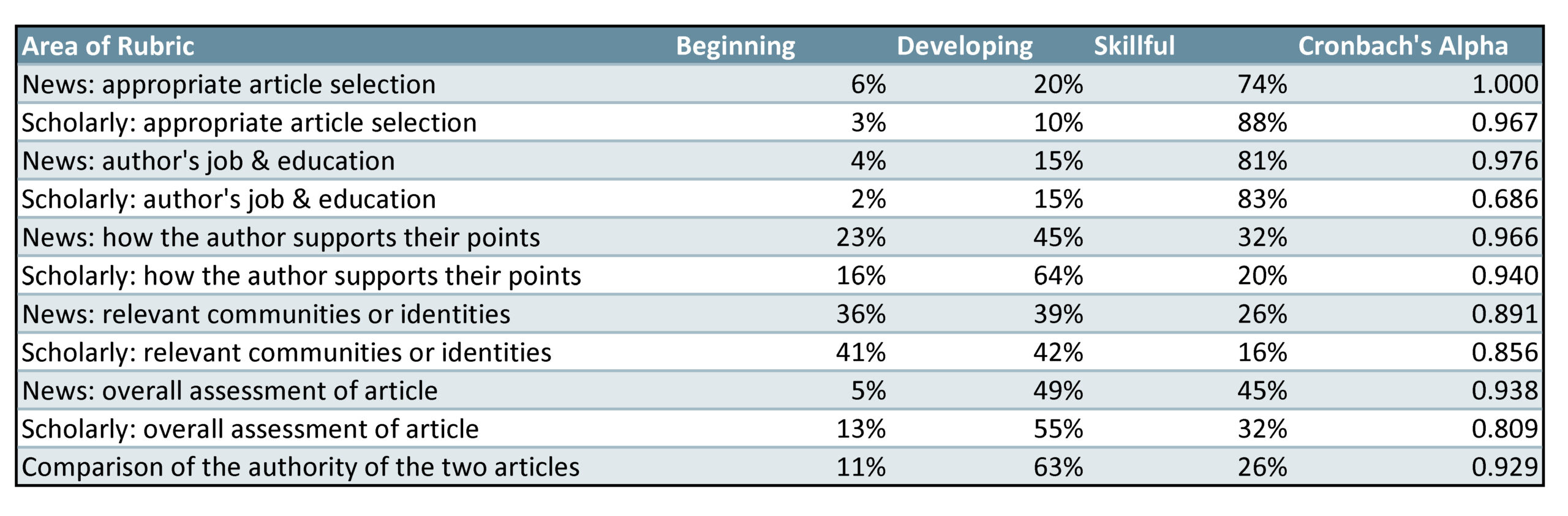

The process for achieving reliability goes like this: everyone who is participating codes the same set of responses, let’s say 10. Then you feed everyone’s codes into statistics software. The software returns a statistic, Cronchbach’s alpha in this case, that indicates how reliably you are all coding together. Based on that reliability score, all the coders work together to figure out where and why you coded differently. Then you clarify the language in the areas of the rubric where you weren’t coding reliably, so you all can hopefully be more consistent the next time. Then you do it over again with a new group of 10 responses and the updated rubric. You have to keep repeating that process until you reach a level of reliability that is acceptable. In this case we used a value of .7 or higher, which is generally acceptable in social science research.

In spring 2021, our scoring and rubric tested as reliable on all 11 areas of the rubric. (We rounded up to .7 for the one area of the rubric that tested at .686.) Then Leah, Kristen, and I worked through all 175 student responses, each coding about 58 pieces of student work. In order to resolve any challenging scores, we submitted scores we felt uncertain about to each other for review. After review, we decided on a final score, which is what was analyzed here. Below you can see the percentage of student scores at different levels for each area of the rubric, as well as the reliability scores for each (Cronbach’s alpha).

We could write a whole different post about the process of coding and creating the rubric. We had many fascinating discussions about what constitutes a news article, how we should score when students have such different background knowledge, discussing our own biases that we bring to the process–including being prone to score more generously or more strictly. We also talked about when students demonstrated the kind of thinking we were looking for but came to a different conclusion than we did, or instances where we thought we understood where they were going with an idea but they didn’t actually articulate it in their response. Evaluating students’ responses was almost as messy and subjective as evaluating the credibility of sources is!

Ultimately, we wanted the rubric to be useful for instructors so that guided the design of the rubric and our coding. “Beginning,” the lowest score, came to represent situations where we thought a student would need significant support understanding the concept. “Developing,” the middle score, indicates that a student understands some of the concept, but still needs guidance. “Skillful,” the highest score, meant that we would be confident in the student’s ability to evaluate this criteria independently. We are excited to present, after all those discussions, such a reliable rubric for your use. We hope it will be a useful tool.

But you don’t have to take my word for it!

We have shared the slides for the lesson, the assignment, and rubric for how to score it. If you would like to use the slides or assignment, please contact Carrie Forbes at the University of Denver. To use the rubric, please reach out to Charissa Brammer at LRS. Have questions? Please reach out. Nothing would delight us more than this information being valuable to you.

On a personal note, this is my last post for lrs.org. I am moving on to another role. You can find me here. I am grateful for my time at LRS and the many opportunities I had to explore interesting questions with the support of so many people. In addition to those already listed in this article, thank you to Linda Hofschire, Charissa Brammer, and everyone at the Colorado State Library for their support of this project.